Cuba's Economic Downfall: Policies that Deepen the Crisis

Why new regulations will only worsen shortages and stifle private enterprise.

Throughout this Substack, I have repeatedly, both implicitly and explicitly, argued that central planning has failed in Cuba. For example, just at the beginning of the month in the article “Food Production and Distribution in Cuba is a Complete Disaster!”, we explored how price controls would worsen the already critical food shortages and how the Castro regime has been reversing its limited market reforms.

Over the summer, however, the central topic of discussion for many Cuban economists has been the economic reforms the regime implemented in 2021, alongside their analysis of inflation trends. Specifically, much debate has centered on how the much-touted economic measures like “La Tarea de Ordenamiento” and the push for Bancarization have rolled back the meager progress made by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Rather than delving into the reasons why both these economic measures have failed to stabilize Cuba’s macroeconomic equilibria, I will focus on why the next wave of policies is also doomed to fail in its attempt to correct “distortions” and “boost the economy.” These policies will likely worsen conditions for Cuban consumers, as the supply of goods and services will continue to shrink at the margins.

Given the Cuban government’s track record, they have failed to set realistic expectations for economic growth or achieve their targets. Looking at the past decade, Cuba has only exceeded its planned growth in 2 out of 13 years, often with poor results.

Recently, Reuters published an article titled “Amid Deepening Economic Crisis, Cuba Tightens Rules on Fledgling Private Sector,” highlighting how the new regulations will severely impact small businesses, retailers, and the self-employed. However, Reuters overlooked a crucial point: the approval of new businesses will now be managed at the municipal level. While this might initially seem like a step towards decentralization, it actually contributes to the already rampant rent-seeking behavior. Now, companies not only need to maintain a favorable stance toward the government but must also align with local party members and bureaucrats, paving the way for corruption, bribes, and local mafia-style practices. This concern is shared by many, including myself.

Another point that could have been added to the Reuters piece is that the regime has expanded its crackdown on the informal currency markets under the guise of fighting “illegal practices.” This campaign, marked by increased persecution of businesses through inspectors, is part of the government’s effort to control the informal exchange rate and curb inflation. While the exchange rate has stabilized somewhat over the past month, there are deeper issues with the regime's macroeconomic policies.

Let’s not forget that just four months ago, the regime was focused on providing macroeconomic stability by increasing aggregate supply. This initiative included legalizing SMEs and deregulating imports. However, due to the government's inability to reduce fiscal deficits, which were instead financed through monetary policy, prices never fell. Moreover, increasing aggregate supply requires time and coordination—neither of which Cuba has the capacity for. Additionally, Cuba lacks open market operations that could enable its central bank to adjustments via the financial side of the economy.1

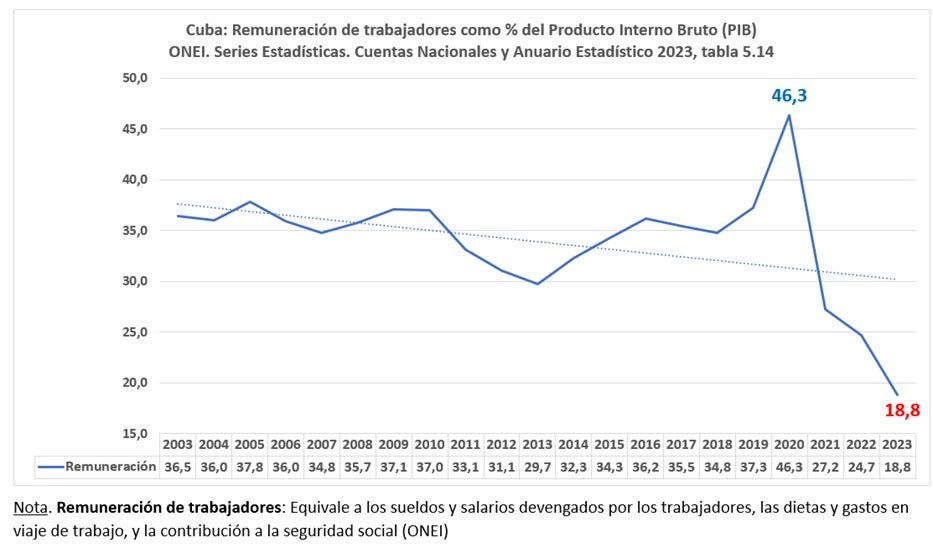

As Pedro Monreal2 has pointed out, the regime has now shifted its strategy from boosting aggregate supply to suppressing demand to extreme levels. This has led to a reduction in worker compensation as a percentage of GDP, further impoverishing the population—89% of whom are now living in conditions of extreme poverty.

Turning to U.S. exports to Cuba, we’ve seen a gradual decline over the past three months, likely reflecting the decreasing capacity of private enterprises to import goods due to new restrictions and political persecution. From June to July alone, there was a 16% drop. As the year progresses, we’ll need to see how these trends unfold, but the regime’s policies are clearly reducing demand, which in turn limits the ability of private enterprises to offer more products. Price controls are compounding this problem by further disincentivizing entrepreneurs to bring key products to the island and creating shortages.

I want to close with some insightful comments from Martin Gurri, a former CIA analyst and current visiting fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, from his article in Discourse magazine titled “In Cuba, the Terminal Stage of Communism is a Mafia.” Gurri describes the regime's rent-seeking practices:

“Corruption can be simple or complex. Officials fortunate enough to have control over scarce resources like fuel sell these on the black market and realize enormous profits. The preferred approach is more indirect, however. Following the outbreak of anti-regime protests in July 2021, the government allowed the establishment of private “micro, small, and medium enterprises,” theoretically as a way to open up the economy to market forces. But most if not all of the 9,000 private enterprises operating in Cuba today are owned by powerful regime figures who then funnel public works contracts to them.”

While I don’t fully agree with the claim that the regime controls all enterprises, there is no doubt that the new regulations are designed to continue favoring the regime’s loyalists while making it increasingly difficult for independent businesses to operate.

Dr. Jose Luis Rodriguez, minister of Economy during the Special Period, propose, among many other things to provide a macroeconomic stabilization program, the creation and issuance of public bonds. Here is the piece.

Professor Pedro Monreal has opened a Substack recently. I would advise you to follow both his Substack and X profile, as he uploads good quality content regarding the state of the Cuban economy.